|

|

|

|

MODEL TEST - ACADEMIC IELTS

(Time: 90 minutes)

|

|

Section 1

Script:

You will hear a man – Martin Hill phoning an Estate Agent in order to find some an accommodation. Cindy: Hello, Brindall's Estate Agents here. How may I help you? Martin: Oh, good morning, I’m ringing to see what flats you have for rent at the moment. Cindy: Right. Can I start by just taking your name Mr em … Martin: Hill, Martin Hill. Cindy: Right, and are you looking for a flat for yourself or ... em ... a family perhaps? Martin: Well it's for three of us: myself and two friends-we're going to share together Cindy: I see ... erm, what about employment - are you all students? Martin: Oh no, we've all got full time jobs - two of us work in the Central Bank, that's Chris and me, and Phil that’s the other one is working for Hallam cars, you know, at the factory about two miles out of town? Cindy: I'll put you down as young professionals, then - and I suppose you'll be looking for somewhere with three bedrooms? Martin: Yeah - at least three. But actually, we'd rather have a fourth room as well if we can afford it - for friends staying over and stuff. Cindy: Is that with a living room to share? Plus kitchen and bathroom? Martin: Yeah, that sounds good. But we must have a bathroom with a shower. We don't mind about having a bath, but the shower's crucial. Cindy: OK, I'll just key that in ... And, are you interested in any particular area? Martin: Well the city centre would be good for me and Chris, so that's our first preference ... but we'd consider anything in the west suburbs as well really - actually for Phil that'd be better, but he knows he's outnumbered! But we aren't interested in the north or the east of the city. Cindy: OK, I'm just getting up all the flats on our books. Choose the correct answer.

|

1. What is Martin′s occupation?

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

2. The friends would prefer somewhere with

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

3. Phil would rather live in

|

|

|

Explain:

|

Script:

Cindy: Just looking at this list here, I'm afraid there are only two that might interest you ... do you want the details? Martin: OK, let me just grab a pen and some paper ... fire away! Cindy: This first one I'm looking at is in Bridge Street - and very close to the bus station. It's not often that flats in that area come up for rent. This one’s got three bedrooms, a bathroom and kitchen, of course ... and a very big living room. That sounds a good size for you. Martin: Mmmm... So, what about the rent? How much is it a month? Cindy: The good news is that it’s only four hundred and fifty pounds a month. Rents in that area usually reach up to six fifty a month, but the landlord obviously wants to get a tenant quickly. Martin: Yeah, it sounds like a bit of a bargain. What about transport for Phil? Cindy: Well, there'll be plenty of buses so no problem for him to use public transport ... or... but unfortunately there isn't a shower in the flat, and that location is likely to be noisy, of course... Martin: OK - what about the other place? Cindy: Let's see ... oh yes, well this one is in a really nice location - on Hills Avenue. I'm sure you know it. This looks like something a bit special. It's got four big bedrooms and erm, there's a big living room and ... oh, this will be good for you a dining room. It sounds enormous, doesn't it? Martin: Yeah, it sounds great! Cindy: That whole area’s being developed, and the flat’s very modern, which I'm sure you’ll like. It’s got good facilities, including your shower. And of course it’s going to be quiet, especially compared with the other place. Martin: Better and better but I’ll bet it’s expensive, especially if it’s in that trendy area beside the park. Cindy: Hmm, I'm afraid so. They're asking £800 a month for it. Martin: Wow! It sounds a lot more than we can afford. Cindy: Well maybe you could get somebody else to move in too? I'll tell you what, give me your address and I can send you all the details and photos and you can see whether these two are worth a visit. Martin: Thanks, that would be really helpful … my address is... Complete the table below. Write NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS AND/OR A NUMBER for each answer. Details of flats available | Location | Features | Good (ü) and bad (×) points | Bridge Street, near the (1)………… | - 3 bedrooms - very big living room | ü £ (2)………… a month ü transport links × no shower × could be (3)………… | (4)………… | - 4 bedrooms - living room - (5)………… | ü (6)……… and well equipped ü shower ü will be (7)……… × £800 a month |

1.

|

very modern/modern

quiet

dining room

£450

Hills Avenue

bus station

noisy

|

Section 2

Script:

Announcer: The Goodwood Museum is currently celebrating some of the most extravagant types of car design in its festival of speed. Here's our reporter Vincent Freed, who's on site, to tell us about some of the cars on display. Reporter: Well, here I am, standing in front of one of the most prestigious cars ever built, the Duesenberg, a fantastically expensive, luxurious car built in the early part of the 20th century and bearing all the glamorous qualities of the jazz age. How many were there? Well, only 473 Duesenberg J-tvpes were ever built and the model here is one of the rarest. Each had a short 125-inch chassis or framework and the body was always in the form of an open two-seater. The technology behind the car's 6.9-litre engine was extraordinary. It featured capsules of mercury in the engines to absorb vibration and provide an incredibly smooth ride. In fact, these cars offered unparalleled performance ... in an age when 160 kilometres per hour was considered very fast, the Duesenberg promised a top speed of 180 kilometres per hour and could do 140 kilometres per hour in second gear. Duesenberg, who designed the car, sold it as a frame and engine ... this was typical of the age again and many prestige manufacturers such as Rolls-Royce did exactly the same. Owners able to afford the hefty $9,000 price tag for the basic car would then commission a coachwork company to build a body tailored to their own individual requirements. The Duesenberg's great attraction for the driver, was its instrument panel which offered all the usual features but also several others including a stop-watch. It was the Duesenberg's technology that lay behind its success as a racing car and they dominated the American racing scene in the 1920s winning the Indianapolis Grand Prix in 1924, '25 and '27. Complete the notes below. Write NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS for each answer. GOODWOOD CAR SHOW Type of car: Dueeenberq J-type Number made: (1)………… Type of body: (2)………… Engines contained capsules of mercury to ensure a (3)………… Top speed: (4)………… per hour. Sold as a (5)………… and Main attraction: (6)…………

1.

|

smooth

180 kilometres

open 2 seater / two-seater/ two seater/2 seater/ open two-seater/ open two seater

frame and engine/ frame engine

473

instrument panel/instruments/stop-watch

|

Script:

On to another celebrity, the 1922 Leyat Helica. Only 30 of these French propellor cars were built and the model here at Goodwood, which was the fourth to be made, is thought to be the only surviving example still capable of running. The brains behind this car was Marcel Leyat who was an aviation pioneer first and foremost, and the influence of flying is quite apparent in the car. The Levat very strongly resembles a light aircraft with its front propellor but in this case it's minus any wings of course! It's quite odd to think that this car was whirring through France, just as the Duesenberg was blasting down roads at 160 kilometres per hour across the Atlantic. The Leyats were used regularly in France in the 1920s and were even produced in saloon and van form, as well as two-seater. The Leyat matched its propellor drive with its equally bizarre steering which used the rear rather than the front wheels! But despite looking rather frail, it was a tough machine. In fact, when troops tried to steal it during the Second World War, the car's baffling design was clearly beyond the would-be thieves and it ended up being driven into a tree, breaking the propellor. And now for the Firebird ... Complete the notes below. Write NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS for each answer. Type of car: Leyat Helica Number built: (1)………… Car looks like a (2)………… without (3)………… Steering used the (4)…………

1.

|

30

rear wheels

light aircraft/plane

wings

|

Section 3

Script:

You will hear the Director of Study in an English language centre and a student representative talking about their Self-Access Centre. PAM: Hi Jun. As you know, I’ve asked you here today to discuss the future of our Self-Access Centre. We have to decide what we want to do about this very important resource for our English language students. So, can you tell me what the students think about this? JUN: Well, from the students’ point of view, we would like to keep it. The majority of students say that they enjoy using it because it provides a variation on the classroom routine and they see it as a pretty major component of their course, but we would like to see some improvements to the equipment, particularly the computers; there aren’t enough for one each at the moment and we always have to share. PAM: Well yes, the teachers agree that it is a very valuable resource but one thing we have noticed is that a lot of the students are using it to check their personal emails. We don’t want to stop you students using it, but we think the computers should be used as a learning resource, not for emails. Some of us also think that we could benefit a lot more by relocating the Self-Access Centre to the main University library building. How do you think the students would feel about that, Jun? JUN: Well, the library is big enough to incorporate the Self-Access Centre, but it wouldn’t be like a class activity anymore. Our main worry would be not being able to go to a teacher for advice. I’m sure there would be plenty of things to do but we really need teachers to help us choose the best activities. PAM: Well, there would still be a teacher present and he or she would guide the activities of the students, we wouldn’t just leave them to get on with it. JUN: Yes, but I think the students would be much happier keeping the existing set-up; they really like going to the Self-Access Centre with their teacher and staying together as a group to do activities. If we could just improve the resources and facilities, I think it would be fine. Is the cost going to be a problem? PAM: It’s not so much the expense that I’m worried about, and we’ve certainly got room to do it, but it’s the problem of timetabling a teacher to be in there outside class hours. If we’re going to spend a lot of money on equipment and resources, we really need to make sure that everything is looked after properly. Anyway, let’s make some notes to see just what needs doing to improve the Centre. Choose a correct answer choice to complete each sentence related to the “Self-Access Centre”.

|

1. Students want to keep the Self-Access Centre because

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

2. Some teachers would prefer to

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

3. The students′ main concern about using the library would be

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

4. The Director of Studies is concerned about

|

|

|

Explain:

|

Script:

PAM: Now, what about the computers? I think it might be a good idea to install some new models. They would take up a lot less room and so that would increase the work space for text books and so on. JUN: That would be great. It is a bit cramped in there at times. PAM: What about other resources? Do you have a list of things that the students would like to see improved? JUN: Yes, one of the comments that students frequently make is that they find it difficult to find materials that are appropriate for their level, especially reading resources, so I think we need to label them more clearly. PAM: Well that’s easy enough, we can get that organised very quickly. In fact I think we should review all of the study resources as some of them are looking a bit out-of-date. JUN: Definitely. The CD section especially needs to be more current. I think we should get some of the ones that go with our latest course books and also make multiple copies. PAM: Good, now I was also thinking about some different materials that we haven’t got in there at all. What do you think of the idea of introducing some workbooks? If we break them up into separate pages and laminate them, they’d be a great resource. The students could study the main course book in class and then do follow-up practice in the Self-Access Centre. JUN: That sounds good. PAM: Okay, now finally we need to think about how the room is used. I’ll have to talk to the teachers and make sure we can all reach some agreement on a timetable to supervise the centre after class. But we also need to think about security, too. Especially if we’re going to invest in some new equipment. JUN: What about putting in an alarm? PAM: Good idea. The other thing I’d like to do is talk to our technicians and see whether we could somehow limit the access to email. I really don’t want to see that resource misused. JUN: What about if we agree to only use it before and after class? PAM: Yes, that would be fine. OK, anyway ... that’s great for now. We’ll discuss it further when we’ve managed to ... Complete the notes below. Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS for each answer. Necessary improvements to the existing Self-Access Centre | Equipment Replace computers to create more space. Resources The level of the (1)............ materials, in particular, should be more clearly shown. Update the (2) ............ collection. Buy some (3) ............ and divide them up. Use of the room Speak to the teachers and organise a (4) ............ for supervising the centre. Install an (5)………... Restrict personal use of (6) ............ on computers. |

1.

|

timetable/ schedule

reading

CD

workbooks

alarm

email/ emails

|

Section 4

Script:

Lecturer: We're going to look today at some experiments that have been done on memory in babies and young children. Our memories, it's true to say, work very differently depending upon whether we are very old, very young or somewhere in the middle. But when exactly do we start to remember things and how much can we recall? One of the first questions that we might ask is - do babies have any kind of episodic memory ... can they remember particular events? Obviously, we can't ask them, so how do we find out? Well, one experiment that's been used has produced some interesting results. It's quite simple and involves a baby, in its cot, a colourful mobile and a piece of string. It works like this. If you suspend the mobile above the cot and connect the baby's foot to it with the string the mobile will move every time the baby kicks. Now you can allow time for the baby to learn what happens and enjoy the activity. Then you remove the mobile for a time and re-introduce it some time from one to fourteen days later. If you look at this table of results ... at the top two rows ... you can see that what is observed shows that two- month-old babies can remember the trick for up to two days and three-month-old babies for up to a fortnight. And although babies trained on one mobile will respond only if you use the familiar mobile, if you train them on a variety of colours and designs, they will happily respond to each one in turn. Now, looking at the third row on the table, you will see that when they learn to speak, babies as young as 21 months demonstrate an ability to remember events which happened several weeks earlier. And by the time they are two, some children's memories will stretch back over six months, though their recall will be random, with little distinction between key events and trivial ones and very few of these memories, if any, will survive into later life. So we can conclude from this that even very tiny babies are capable of grasping and remembering a concept. Complete the notes below. Write NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS or A NUMBER for each answer. Question: Can babies remember any (1)………? Experiment with babies: Apparatus: baby in cot colourful mobile some (2)……… Re-introduce mobile between one and (3)……… later. Table showing memory test results Baby’s age | Maximum memory span | 2 months | 2 days | 3 months | (4)……… | 21 months | several weeks | 2 years | (5)……… |

1.

|

a fortnight/2 weeks/two weeks/ fortnight/14 days

14 days/ a fortnight/2 weeks/two weeks/ fortnight

six months/ 6 months

particular events/ events

string

|

Script:

So how is it that young infants can suddenly remember for a considerably longer period of time? Well, one theory accounting for all of this - and this relates to the next question we might ask - is that memory develops with language. Very young children with limited vocabularies are not good at organising their thoughts. Though they may be capable of storing memories, do they have the ability to retrieve them? One expert has suggested an analogy with books on a library shelf. With infants, he says, 'it is as if early books are hard to find because they were acquired before the cataloguing system was developed'. But even older children forget far more quickly than adults do. In another experiment, several six-year-olds, nine-year- olds and adults were shown a staged incident. In other words, they all watched what they thought was a natural sequence of events. The incident went like this ... a lecture which they were listening to was suddenly interrupted by something accidentally overturning, in this case it was a slide projector. To add a third stage and make the recall more demanding, this 'accident' was then followed by an argument. In a memory test the following day, the adults and the nine-year-olds scored an average 70% and the six- year-olds did only slightly worse. In a retest five months later, the pattern was very different. The adults' memory recall hadn't changed but the nine-year-olds' had slipped to less than 60% and the six-year-olds could manage little better than 40% recall. In similar experiments with numbers, digit span is shown to... Complete the notes below. Write NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS or A NUMBER for each answer. Research questions: Is memory linked to (1)……… development? Can babies (2)……… their memories? Experiment with older children: Stages in incident: a) lecture taking place b) object falls over c) (3)……… Table showing memory test results Age | % remembered next day | % remembered after 5 months | Adults | 70% | (4)…………% | 9-year-olds | 70% | Less than 60% | 6-year-olds | Just under 70% | (5)…………% |

1.

|

40

an argument/ argument

language

70

retrieve/recall/recover

|

Passage 1

THE ROCKET - FROM EAST TO WEST (A) The concept of the rocket, or rather the mechanism behind the idea of propelling an object into the air, has been around for well over two thousand years. However, it wasn’t until the discovery of the reaction principle, which was the key to space travel and so represents one of the great milestones in the history of scientific thought, that rocket technology was able to develop. Not only did it solve a problem that had intrigued man for ages, but, more importantly, it literally opened the door to exploration of the universe. (B) An intellectual breakthrough, brilliant though it may be, does not automatically ensure that the transition is made from theory to practice. Despite the fact that rockets had been used sporadically for several hundred years, they remained a relatively minor artifact of civilisation until the twentieth century. Prodigious efforts, accelerated during two world wars, were required before the technology of primitive rocketry could be translated into the reality of sophisticated astronauts. It is strange that the rocket was generally ignored by writers of fiction to transport their heroes to mysterious realms beyond the Earth, even though it had been commonly used in fireworks displays in China since the thirteenth century. The reason is that nobody associated the reaction principle with the idea of travelling through space to a neighbouring world. (C) A simple analogy can help us to understand how a rocket operates. It is much like a machine gun mounted on the rear of a boat. In reaction to the backward discharge of bullets, the gun, and hence the boat, move forwards. A rocket motor’s ‘bullets’ are minute, high-speed particles produced by burning propellants in a suitable chamber. The reaction to the ejection of these small particles causes the rocket to move forwards. There is evidence that the reaction principle was applied practically well before the rocket was invented. In his Noctes Atticae or Greek Nights, Aulus Gellius describes ‘the pigeon of Archytas’, an invention dating back to about 360 BC. Cylindrical in shape, made of wood, and hanging from string, it was moved to and fro by steam blowing out from small exhaust ports at either end. The reaction to the discharging steam provided the bird with motive power. (D) The invention of rockets is linked inextricably with the invention of ‘black powder’. Most historians of technology credit the Chinese with its discovery. They base their belief on studies of Chinese writings or on the notebooks of early Europeans who settled in or made long visits to China to study its history and civilisation. It is probable that, some time in the tenth century, black powder was first compounded from its basic ingredients of saltpetre, charcoal and sulphur. But this does not mean that it was immediately used to propel rockets. By the thirteenth century, powder- propelled fire arrows had become rather common. The Chinese relied on this type of technological development to produce incendiary projectiles of many sorts, explosive grenades and possibly cannons to repel their enemies. One such weapon was the ‘basket of fire’ or, as directly translated from Chinese, the ‘arrows like flying leopards’. The 0.7 metre-long arrows, each with a long tube of gunpowder attached near the point of each arrow, could be fired from a long, octagonal-shaped basket at the same time and had a range of 400 paces. Another weapon was the ‘arrow as a flying sabre’, which could be fired from crossbows. The rocket, placed in a similar position to other rocket-propelled arrows, was designed to increase the range. A small iron weight was attached to the 1.5m bamboo shaft, just below the feathers, to increase the arrow’s stability by moving the centre of gravity to a position below the rocket. At a similar time, the Arabs had developed the ‘egg which moves and burns’. This ‘egg’ was apparently full of gunpowder and stabilised by a 1.5m tail. It was fired using two rockets attached to either side of this tail. (E) It was not until the eighteenth century that Europe became seriously interested in the possibilities of using the rocket itself as a weapon of war and not just to propel other weapons. Prior to this, rockets were used only in pyrotechnic displays. The incentive for the more aggressive use of rockets came not from within the European continent but from far-away India, whose leaders had built up a corps of rocketeers and used rockets successfully against the British in the late eighteenth century. The Indian rockets used against the British were described by a British Captain serving in India as ‘an iron envelope about 200 millimetres long and 40 millimetres in diameter with sharp points at the top and a 3m-long bamboo guiding stick’. In the early nineteenth century the British began to experiment with incendiary barrage rockets. The British rocket differed from the Indian version in that it was completely encased in a stout, iron cylinder, terminating in a conical head, measuring one metre in diameter and having a stick almost five metres long and constructed in such a way that it could be firmly attached to the body of the rocket. The Americans developed a rocket, complete with its own launcher, to use against the Mexicans in the mid-nineteenth century. A long cylindrical tube was propped up by two sticks and fastened to the top of the launcher, thereby allowing the rockets to be inserted and lit from the other end. However, the results were sometimes not that impressive as the behaviour of the rockets in flight was less than predictable. (F) Since then, there have been huge developments in rocket technology, often with devastating results in the forum of war. Nevertheless, the modern day space programs owe their success to the humble beginnings of those in previous centuries who developed the foundations of the reaction principle. Who knows what it will be like in the future?

Choose the most suitable headings for paragraphs.

Choose the appropriate answers.

|

1. The greatest outcome of the discovery of the reaction principle was that

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

2. According to the text, the greatest progress in rocket technology was made

|

|

|

Explain:

|

Choose the appropriate answers indicating who FIRST invented or used the items.

|

2. rocket-propelled arrows for fighting

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

3. rockets as war weapons

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

4. the rocket launcher

|

|

|

Explain:

|

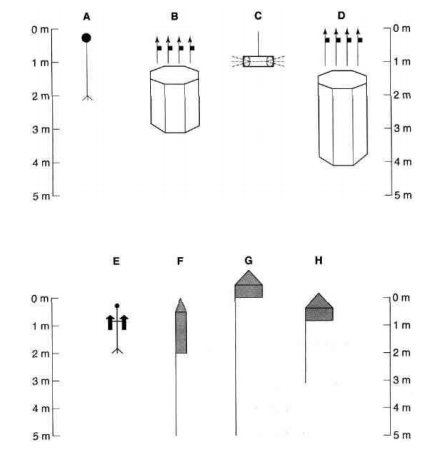

Look at the drawings of different projectiles below, A-H. Choose the right answers for names of types of projectiles.

|

1. The Greek ‘pigeon of Archytas′

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

2. The Chinese ‘basket of fire′

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

3. The Arab ‘egg which moves and burns′

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

4. The Indian rocket

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

5. The British barrage rocket

|

|

|

Explain:

|

Passage 2

Sustainable growth at Didcot: the outline of a report by South Oxfordshire District Council (A) The UK Government’s South East Plan proposes additional housing growth in the town of Didcot which has been a designated growth area since 1979. We in South Oxfordshire District Council consider that, although Didcot does have potential for further growth, such development should be sustainable well-planned, and supported by adequate infrastructure and community services. (B) Recent experience in Didcot has demonstrated that large greenfield* developments cannot resource all the necessary infrastructure and low-cost housing requirements. The ensuing compromises create a legacy or local transport, infrastructure and community services deficits, with no obvious means of correction. We wish to ensure that there is greater recognition of the cost attached to housing growth, and that a means is found to resource the establishment of sustainable communities in growth areas. (C) Until the 1950s, the development of job opportunities in the railway industry, and in a large, military ordance, was the spur to Didcot’s expansion. Development at that time was geared to providing homes tor the railway and depot workers, with limited investment in shopping and other services for the local population. Didcot failed to develop Broadway as a compact town centre, and achieved only a strip of shops along one side of the main street hemmed in by low density housing and service trade uses. (D) From the 1970s, strategic planning policies directed significant new housing development to Didcot. Planners recognised Didcot’s potential, with rapid growth in local job opportunities and good rail connections for those choosing to work farther afield. However, the town is bisected by the east-west railway, and people living in Ladygrove, the urban extension to the north which has been built since the 1980s, felt, and still feel, cut off from the town and its community. (E) Population growth in the new housing areas failed to spark adequate private-sector investment in town centre uses, and the limited investment which did take place - Didcot Market Place development in 1982, for instance — did not succeed in delivering the number and range of town centre uses needed by the growing population. In 1990, public-sector finance was used to buy the land required for the Orchard Centre development, comprising a superstore, parking and a new street of stores running parallel to Broadway. The development took 13 years to complete. (F) The idea that, by obliging developers of new housing to contribute to the cost of infrastructure and service requirements, all the necessary finance could be raised, has proved unachievable. public finance was still needed to deliver major projects such as the new link road to the A34 on the outskirts of the town at Milton, the improved railway crossing at Marsh Bridge and new schools. Such projects were delayed due to difficulties in securing public finance, the same problem also held back expansion of health and social services in the town. (G) In recent years, government policy, in particular the requirement for developers that forty percent of the units in a new housing development should be low cost homes, has had a major impact on the economics of such development, as it has limited the developers contribution to the costs of infrastructure. The planning authorities are facing difficult choices in prioritising the items of infrastructure which must be funded by development, and this, in turn, means that from now on public finance will need to provide a greater proportion of infrastructure project costs. (H) The Government’s Sustainable Communities Plan seeks a holistic approach to new urban development in which housing, employment, services and infrastructure of all kinds are carefully planned and delivered in a way which avoids the infrastructure deficits that have occurred in places like Didcot in the past. This report, therefore, is structured around the individual components of a sustainable community and shows the baseline position for each component. (I) Didcot has been identified as one of the towns with which the Government is working to evaluate whether additional growth will strengthen the economic potential of the town, deliver the necessary infrastructure - A programme of work, including discussions with the local community about their aspirations for the town as well as other stakeholders will be undertaker over the coming months, and will lead to the development of a strategic master plan. The challenge be in optimising scarce resources to achieve maximum benefits for the town. * land that has never previously been built on

Which paragraph contains the following information?

|

1. reference to the way the council′s report is organised

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

2. the reason why inhabitants in one part of Didcot are isolated

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

3. a statement concerning future sources of investment

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

4. the identification of two major employers at Didcot

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

5. reference to groups who will be consulted about a new development plan

|

|

|

Explain:

|

|

6. an account of how additional town centre facilities were previously funded

|

|

|

Explain:

|

Match each place with the correct statement.

|

3. Orchard Centre

|

|

|

Explain:

|

Complete the sentences below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer

1.

|

strategic master plan

infrastructure

low cost/affordable

|

Passage 3

Jo-Anne Everingham | The infamous Sardar Sarovar Dam on the Narmada River in India was initiated with World Bank loans. It was designed primarily to irrigate 1.8 million drought-prone hectares in the state of Gujarat. Despite the extensive canal and pipeline network, the 20 million people in Gujarat have this year experienced their worst drought for a century. When I visited in April more than half its villages- almost 10,000—were drought-declared. Virtually all the state government water reservoirs had dried up, and emergency water-tanker distribution, new bore drilling, well-deepening and pipeline extensions were underway. Yet only nineteen of the 243 wells dug in one district struck water-some were still dry at 150 metres. Many dairy cattle had died and the remainder were giving very little milk. While I was there, newspaper headlines announced the first human casualties. The state government had set up 3000 relief work projects employing 450 000 people, and a range of NGOs had formed a network to lobby the state and national governments on people's small-scale solutions to water- related hardship. One such organization is Community Aid Abroad-Oxfam Australia partner Mahiti Sanstha, which works with around 20 000 people in the Bhal region. Villages in the Bhal region are located in the low-lying sandy, semi-arid and very drought- prone coastal parts of the Saurashtra area. Most are clusters of mud-walled, tile and thatch-roofed huts on flat, saline plains, with between one and two and a half thousand inhabitants. The population is about 60% Koli Patels—ex-fisherfolk who are now tenant farmers, 25% Darbars-a high-caste landowning group who dominate most villages, and 15% other castes and Dalits, or outcasts. In the 60 or so villages where they work, Mahiti forms two kinds of groups: water management committees and women's self help groups. I met 58 women who made up the self help group in Sandhida village. They described how they had all been both isolated and hopelessly indebted five years ago. Now, their solidarity gives them 'the strength of 58 women'-a strength they have used to pressure the local 'collector' and the Darbars in their community. All the village girls now attend the local primary school, while six girls and four boys are away at secondary school. Yet in nearby Khungam village we met young girls working as diamond cutters. They have no opportunity to go to school and were still at work after dark. There is still much work for Mahiti to do. | Water management committees in the villages where Mahiti works are made up of four women and three men. Water is an all- consuming concern for most women, whose day is structured around various trips to collect water for home and livestock, or around the arrival of the government water tankers every eight days in those villages whose water supply has dried up. In some villages, the committees have organised to deepen the village 'tanks'-or dams-and line them with plastic, which stops water salination and reduces seepage and evaporation. We saw some lined tanks still holding a few weeks' water supply when conventional dams were dry. Mahiti is now sponsoring trials of various pumping and filtering arrangements for the tanks, to counter the silt and often collapsing walls. Many self help groups also loan funds to members who want to use a government incentive scheme for installing roof-water tanks. Those who can put up 30 percent of the cost receive the remainder as a subsidy. In Rajpur, a hamlet with few government facilities-no electricity, inadequate roads, no water pipeline, no school teacher or primary healthcare centre — half the 37 families belonging to the self help group now have these tanks. Most people in Rajpur work as tenant farmers. Mahiti told them: 'If you bring all your 80 families united in one meeting, it will change your lives in three years.’ When the Darbars [the upper castes] want something, they are united and they get it in three years.' At every village we visited in the Bhal region, women gave us an overwhelming welcome. Their struggle against the hardship of the drought is constant, and their poverty is grinding. These women work in the fields whenever one of the big landowners will hire them for the one cropping season possible each year in the region. At best they earn around 3 rupees, or AUD1.50 a day, and they're lucky to average 14 days work a month. Most are up at six to cook, clean, and manage the household and livestock not only for their nuclear family but often for some inlaws as well. Their energy and determination, along with the information and training Mahiti can provide and resources from Community Aid Abroad-Oxfam Australia is making a real difference at the community level, with 'small is beautiful', practical, equitable and environmentally sustainable strategies to conserve water. |

Choose the appropriate answer.

|

1. Choose the most appropriate title for the reading passage.

|

|

|

Explain:

Choice “Drought: Small Scale Solutions for a Very Big Problem” is the best choice. Choice “Water: A Woman's Work” is not appropriate because, while women are active in collecting water, it is an issue for the whole community. C would be inaccurate as the passage clearly states that the dam is NOT providing water for all. Choice “Dams: Providing Water for All” is also too general suggesting all dams, while this passage is only about one dam. D would also not be accurate because the major part of the passage describes ways people are solving the problems related to drought. |

|

2. Gujarat has approximately how many villages?

|

|

|

Explain:

Paragraph one states, ‘...more than half its villages-almost 10,000...', so there must be approximately 20,000 villages. |

|

3. Water management committees′ tasks include

|

|

|

Explain:

Women collect water for home and livestock, subsidies are provided for water tanks. However, who installs them is not clear. Water pipelines have been installed by governments. |

|

4. Which group has been most successful in tackling the water problems in Gujarat?

|

|

|

Explain:

All these groups have been successful in some way. However, ‘local groups' is the main point that encompasses women and NGOs. |

Do the following statements reflect the information in the reading passage?YES if the statement reflects the information in the passage NO if the statement contradicts the information in the passage NOT GIVEN if there is no information about this in the passage

|

1. The Sardar Sarovar Dam is providing water to 20 million people.

|

|

|

Explain:

The dam has failed to provide enough water resulting in continuing water problems. |

|

2. State and national governments are funding small-scale projects aimed at water- related problems.

|

|

|

Explain:

Groups have lobbied these governments however it is not clear whether this lobbying has been successful. |

|

3. Women′s self help groups have been successful in improving education for girls in some villages.

|

|

|

Explain:

The end of paragraph two states that, ‘All the village girls now attend the local primary school, while six girls and four boys are away at secondary school.' This statement follows immediately after the information that the forming of a self-help group had given the women the strength to improve the life of their communities. By implication, the women can be considered instrumental in enabling the girls to attend school. |

|

4. Water tanks and dams lined with plastic is one means of preserving water which is working.

|

|

|

Explain:

Paragraph three states, ‘In some villages, the committees have organised to deepen the village “tanks”-or dams-and line them with plastic, which stops water salination and reduces seepage and evaporation. We saw some lined tanks still holding a few weeks' water supply when conventional dams were dry.' |

Complete the summary of the reading passage. Choose your answers from the table. NB: There are more words/phrases than you will need to fill the gaps. You may use a word or phrase more than once if you wish. extending | deepening | managed | management | bores | incentive | assistance | tankers | casualties | succeeded | limits | supplies |

1.

|

supplies

tankers

extending

succeeded

casualties

|

| No. | Date | Right Score | Total Score |

|

|

|

PARTNERS |

|

|

NEWS |

|

|

|

|

|

|